Analogy as a Demon: The Material and Process of Plastic

This article, written by Alfredo Aracil and Hernán Borisonik, was proposed to us by Anfibia as part of our second Lovework Open Call. It is one of a collection of pieces that explore the overlap between science and metaphor around various elements: water, fire, and plastic.

“…an object only exists by being broken down into a series of analogies.”

Proust

1.

No one with a shred of intellect can claim to know what will ultimately become of plastic in its many forms.

This patchwork of text – made up of layered readings and understandings of various works and lives beyond those of plastic itself – was conceived of as an exercise in speculative research that does not seek to be a coherent and conclusive work of critical theory. This attempt to ponder and understand plastic without attempting to explore it in its infinite totality, but rather as the site of a new world of ecology, began with an exhibition at the Fundación Andreani in Buenos Aires, where artists Nicolas Gullota and Alín Grad approached plastic as an artificial and alien part of nature: on the one hand, a body that readily invades other bodies and colonises new territory, and on the other, a mysterious force with the power to turn terrifying fictions into reality.

In what follows, we will explore different conspiracies in order to create spaces of understanding between humans and plastic. Opening channels of communication through its arsenal of cultural, media-based and narrative avatars, this text is, in one way, an attempt to make contact with a substance that eludes or evades reason. Because of its inherently boundless, transformative nature, plastic challenges the categories most commonly used to catalogue life and understand its ultimate meaning. In another way, however, reason and plastic contaminate one another, and even merge to form something new. After all, there are few things more malleable than history and reason. Plastic embodies totality and waste, nature and history, external and internal limits. Like a new skeleton that envelops us, erasing any difference between inside and out, it speaks in a language of hydrocarbons, geological forces and tectonic plates in perpetual movement, amplifying the echoes of past, present and future disasters.

In order to understand a shadow, one must manipulate the light source behind it. It is precisely in this way that we would like to appropriate some of the functional and behavioural tendencies of plastic to present it as an entity that, from a western theological and metaphysical perspective, can be seen as a demon because of how it confounds bodies and nature. We start from the notion of plastic as a strange object – with myriad names, faces, and shapes – that, after thousands of years in silence, now interrogates us about what can no longer be kept silent regarding the manifold crises we find ourselves in today: climate change, food insecurity, energy shortages, debt, and financial disaster.

2.

Although rather aristocratic in nature, the first symptoms of industrial civilisation emerged as depression and tuberculosis. Among the masses, byssinosis was caused by the inhalation of cotton on the slave plantations of the 18th century, and in the 19th century, the first cases of silicosis appeared in dark coal mines. With the subsequent modernisation of working-class homes, natural gas substituted coal in domestic settings. This change of energy model had an unexpected effect: we stopped receiving visits from ghosts in our homes at night because we were no longer exposed to carbon monoxide while sleeping.

In the 20th century, when, as Barthes wrote, “the artificial became commonplace, rather than exclusive,” the development of plastic was fundamental in certain lifestyle-based processes of globalisation and standardisation, from pantyhose to the replacement of reconstructive surgery (designed to “fix”) with plastic surgery (designed to “create”). We began to understand our own bodies as a malleable, plastic canvas. Plastic took on a global scale through innovations in the field of war, after which it was very quickly and directly applied to the world of consumerism and well-being, with the promise of upward social mobility. In the arts and emerging visual culture – including everything from photography and film to the conceptual experiments of Marcel Duchamp – plastic was key to the revolutionary development of pigments that fueled monochromatic postmodern painting. However, due to its commonplace nature, and except for certain unique stylistic developments such as pop art and the work of Brazilian artist Lygia Clark, plastic never attained the same status as other, more respectable materials that come directly from the earth. Thus, plastic has maintained a degree of invisibility, relegated to the stages of production and assembly that lead up to the celebratory moment of exhibition.

In this era, which authors like Jason Moore call the Capitalocene, capitalism is no longer conceptualised or experienced as an economic system, but rather as a way of organising and producing nature. There is a certain plasticity in how we think and perceive that, in turn, transforms our emotions and perceptions, our dreams and our restfulness. With the accumulation of wealth seemingly both everywhere and nowhere, like plastic itself, it begins to resemble the metamorphic extraterrestrial substance in John Carpenter’s 1982 film The Thing. Working has ceased to be synonymous with having a salary, but instead entails living in a continual state of availability and paranoia.

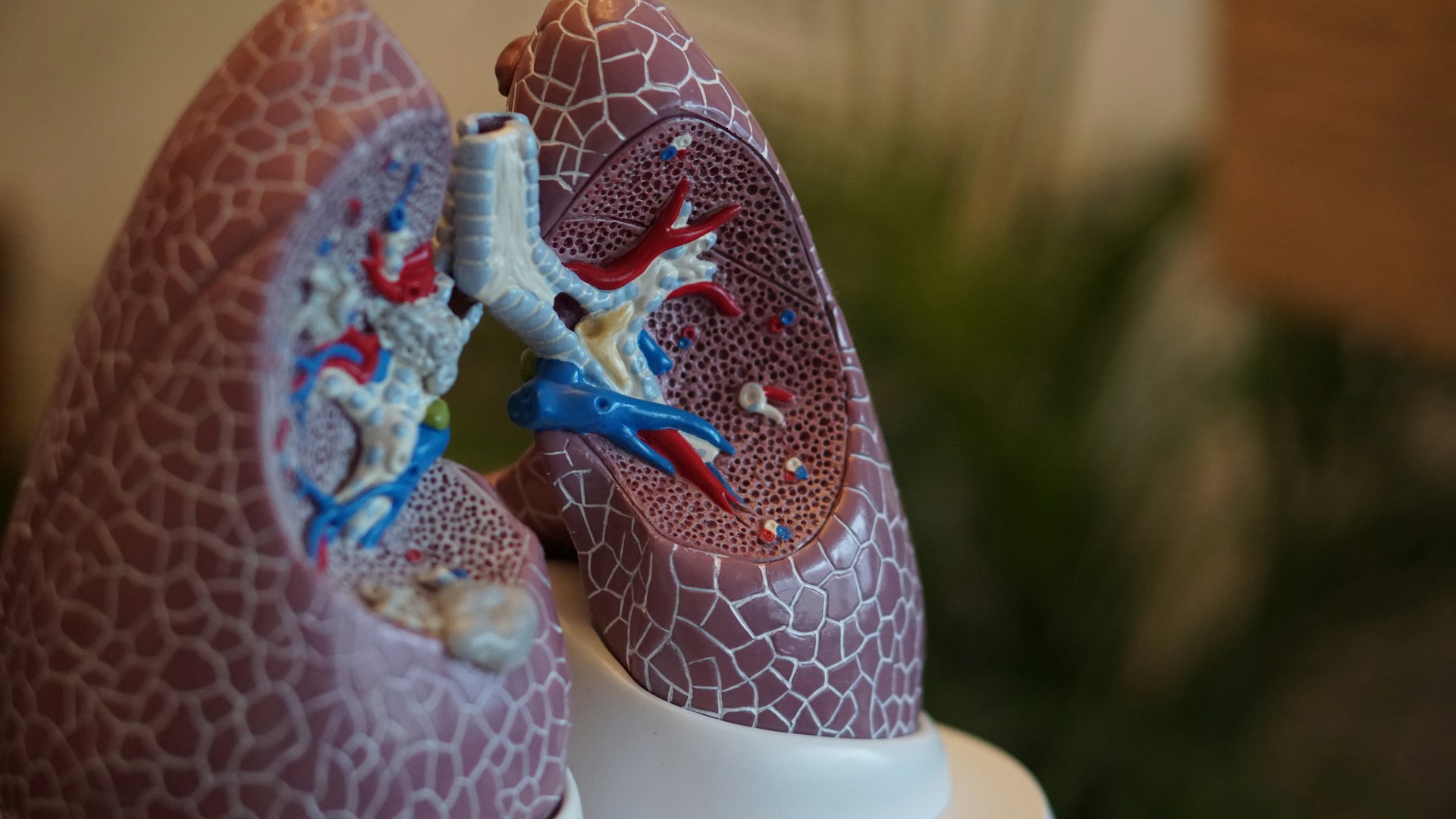

Our lungs are exposed to air that is becoming denser, more suffocating, and more toxic by the minute. We know very well the effects of hydrocarbons. We know of the side-effects experienced throughout the world from bombs and atomic energy disasters, and little by little, studies are appearing on the consequences of the emissions generated by the manufacture and infrastructure of digital technology. While it is still too early to determine the effects of atmospheric microplastics travelling thousands of kilometres through air currents that once transported pollen, dust is matter in its most minute form, and it goes where the wind takes it. Out of thin air, particles of plastic appear in the stomachs of fish in our oceans, in the intestines of our housepets, and in the cells of foetuses. This material colonisation – whether in trace or excessive amounts – is already affecting the growth, photosynthesis, and production of oxygen in prochlorococcus, the submarine photosynthetic bacteria responsible for eliminating one tenth of the CO2 in the air we breathe.

By seeing nature as something passive and external to ourselves – in order to maintain the myth of progress and the belief that we must have unfettered, permanent access to all information on the planet – we willingly contribute to entities that, according to all sources, damage our health via a system of accumulation in which our minds, linguistic abilities, bonds and senses are merely commodities that can be capitalised on. What, then, about spiritual matters? What effect does this plastic imperialism have on our species’ most distinctive internal world? Will the remnants of humankind – growing ever smaller as the agency of immortal and immoral materials grows – be able to accept that, just as steel needed fascism in order to develop and transform reality, plastic requires us to design a new world? A world, built in its image and likeness, that suits its own needs, in which we will very soon be the anomaly (if we aren’t already).

What, then, would happen if we abandoned the green approach of completely denouncing plastic? Can we accept, beyond catastrophisation and disheartening deadlines that determine the fate of our biosphere, that geology is a co-producer of power? If instead of xenophobia and fear mongering about poisonous fumes, we adopted the perspective of fiction, if we embraced “the creative, generative and multi-layered relation of species and environment”, as Jason Moore says in Capitalism in the web of life, would it be possible to experience the final stages of human sovereignty on Earth not as an end-of-life drama or a planet devoid of humans, but rather as an ontological shift towards an unprecedented future horizon for our species?

In the case of the blackish powder that alchemists used to transform impure substances into gold, involvement with non-human and inorganic substances was an embodiment of both demonic shadow – for being poisonous and even lethal – and a means to stimulate a process of transformation. This, in turn, would serve to create more breaches and points of passage in the divide between being and not being, life and death, everything and nothing. Perhaps for this and other reasons, Roland Barthes defined plastic as “essentially an alchemical substance”. He goes even further, dubbing it “a miraculous material”, “ubiquity made visible” and “sublimated as movement”.

3.

After reading and debating philosopher German Prósperi, we can reach the always transitory conclusion that the behaviour of plastic maintains a relationship with the itinerant life of images. From the beginning, both images and plastic are subtle elements that are dispersed through the air like a virus: they are neither organisms nor inert substances. They both hold an incredible capacity for metaphor, which, at some point, inevitably renders them demonic. For many priests in the Church, the demon was one of a thousand faces and forms. The demon is multiplicious, able to assume human, animal and vegetable form. It can change into a colour or disperse into mist. Psyche, eidolon, phantasma, genie, spectre, daimon, diabolon, and so on. However, plastic was not created by the gods, but by humans. It is a technical synthetic, and therefore artificial. One only need glance up from this text to see the complete ubiquity of plastic. Nowadays, there is more plastic than there are people, and between the two of us, we humans are the ones who are likely to disappear. After all, plastic has its own finiteness. A half-litre plastic bottle takes more than 500 years to decompose. Plastic can do nothing beyond existing. It is visible and tangible. Its physicality is post-human.

Reportedly, 99% of plastics are produced from petroleum and natural gas. These artificial polymers, easy to modify and suitable for the commercial world on a large scale. They can be moulded into any shape. They tend to be light and affordable, and they can be complemented by added substances that improve on properties such as resistance and durability. However, classical philosophy has tended to separate material from form, and see analogies as something monstrous. If there is something truly suspicious about plastic, it is its phantasmic nature. Characteristic properties of certain plastics – such as high thermal conductivity, temperature resistance, expansion, specific heat capacity, and high temperatures of vitrification – give us some hints into the cultural terror produced by this ghost-like substance in our still very humanist mentality.

On city streets, affixed to everything around us and even in the air we breathe, we find plastic sediment in suspension. A low dose of toxic dust. Even worse, it is not one single material, but rather a multitude of materials swarming together, ignorant of the relationships between humans and non-humans, of the transportation of minerals and metals that affect realms such as the economy, politics and even the health of the planet. Lead, chromium, soot, a myriad of gases, a fine layer of nitrates, hydrocarbons… At every traffic light, cars spit out particles of microplastics given off into the atmosphere by deteriorating brakes. We breathe this dust of chemicals, both organic and inorganic, but we also inhale and exhale the dust of the cosmos, made of materials from other planets.

This seeming paradox was explored by Björk in the mid-1990s. For her, technology and nature could ultimately be the same thing, and if that is the case, we are obligated to reassess the relationship between the past and the future. In fact, looking at a pastoral painting of a wooden house in the mountains, any group of non-human mammals such as monkeys would perceive a wondrous technological construction, a futuristic archaeological find of sorts. However, if a group of humans looks at the same painting, it will be perceived as a representation of nature in all its splendour. Nevertheless, the point is not whether or not the scene was created by the hand and mind of a human; it is instead about being able to navigate, via the medium of art, between the two poles of technology and nature, and thereby exist in the being and now of things themselves.

4.

“Every particle of dust carries with it a singular vision of material, movement, collectivity, interaction, fondness, separation, composition and infinite darkness.”

Reza Negarestani, Ciclonopedia.

“The means opens up possibilities,” says Belgian author Vinciane Despret in his book on the health of the dead, where he also raises a key question: What do we know about what the body continues to feel once it stops breathing? How would painter, parapsychologist, opera singer and filmmaker Friedrich Jürgenson respond to such a subtle question? On the morning of June 12, 1959, in Stockholm, Jürgenson recorded birdsong in the countryside near his house. After a session of what today we would call field recording, he played back the tape, listened, and was surprised to hear the whispering of acquaintances who had died, as well as many other voices and manifestations of sound, almost inaudible, made by other people whom he did not know at all. This way of tuning into spiritual matters and the echoes of another world – tuning into life after the flesh is long decomposed – represents a mysterious aspect of progress and the development of electronic media. An important B-side that contrasts with many naïve anthropological studies tells of how the boom of the Spiritualists at the dawn of the 20th century ran parallel to the proliferation of electromagnetic fields created by “artificial” electric charges that managed to eclipse the ability of supernatural beings, such as vampires and ghosts, to pursue and commune with the living.

Sound artist Ailin Gran (a.k.a. Aylu) inspired us to explore this history. It turns out that Jürgenson met with an unhappy fate, as his life after that spiritualist event took a turn for the worse. Looking for a title for her presentation in the Fundación Andreani exhibit that inspired this essay, Ailin proposed the word “acousmatics”, which refers to sound compositions that only exist as audio recordings and that, by means of electronic synthesis, focus the listener’s attention on an object that can be heard without being able to discern the source of the sound. Indeed, the word “vinyl”, a type of plastic, is still synonymous with recorded music. Aylu’s work, in the context of a visual arts exhibition, evokes an uncomfortable synaesthesia in which the space turns into a plastic whole that penetrates the ears like prāṇa and leaves no room for a monopolistic focus on other kinds of images. With ears full, everything in the room dances, compelled, like the origin of plastic, by supernatural forces. The perfect companion for this state of geological psychedelia is one of of Nicolás Gullotta’s creations, which at first glance appears to be a rug made of plastic. The misperception of materials stems from the insufficiency of our vision to capture the worlds inhabited by the material. In his work, we always find the question of how perception, something that seems so natural, is actually fabricated. This is not the first time that his work opens up to the minuscule, the poetics of industrial excess. His piece speaks of what remains, what is left over and cannot be measured, that which is lost and impossible to grasp, the wasted energy that cannot be reused for anything else. In the end, isn’t a rug ridden with toxic plastic dust that cannot be stepped on just a painting lying on the floor? Either way, the visual space is filled with other information that appeals to the indirect, the mediated, to the sense of senses that, as Aristotle said, captures second-hand what our sensory organs perceive directly.

A sentient being – albeit anonymous and impassive in appearance, especially in the face of ordinary language and its emotive or phatic functions – plastic was synthesised “for the first time” in the mid-19th century. The never ending and unforeseen development of plastic as part of a lineage of oil, the “eternal lubricant” as it was called in ancient Mesopotamia, brings us closer to an expanded understanding of time and of the senses. Studying plastic entails thinking about processes that last much longer than human life, processes whereby the ability to act remains alive and well for millenia. In fact, as Einstein demonstrated with his theory of relativity, time itself is plastic, both conceptually and existentially as an element of space. History, understood as that which is determined by the ebb and flow of plastic, can be considered a spectral entity that haunts us from the deepest most subterranean past in order to cannibalise what was once called Nature. From this point of view, the future will most certainly become ever more plastic in nature.

5. Conclusion

As millions of plastic particles slowly and imperceptibly fell on the trees and grass of the Valle Hermoso nature reserve in Cordoba, philosopher Raúl Rodríguez Freire gave the idea of recycling a conceptual twist. The first criticisms of plastic can be compared to Plato’s great abhorrence for mimesis (and analogy) as a political force. In both cases, the focus was on artificiality and the lack of contribution made by that which does not stem from a world before humanity. Nevertheless, nothing in our current world would exist without plastic, from prosthetics to cars, colours, clothing, and toys. Almost everything surrounding us is made of either high or low density polyethylene. Plastic is our greatest metaphor, the stuff of philosophy and politics.

Without plastic there is no second or third Mother Nature, there is neither ecology nor language.

Far beyond the concept of cerebral plasticity, an idea celebrated since the end of the 20th century, anything that can be reconfigured can be said to be plastic. Every time we think about how to do something in a way that differs from how it was done before, which is the lifeblood of artistic expression, we strive for plasticity. What are perspective and representation if not forms of plasticity and adaptation? Plastic confronts us with a Herculean conundrum: When nothing is fixed and everything is malleable, what static points of reference remain? And finally, what possibilities do we have to say “no” in a plastic world, one that that incessantly pulls and stretches us in every conceivable direction?

![]()

Produced by Guerrilla Translation under a Peer Production License

– Translated by Timothy McKeon

– Edited by Alex Minshall

– Header image by hartono subagio on Pixabay

– Image 2 by Robina Weermeijer on Unsplash

– Image 3 by Hans on Pixabay

– Image 4 by Daniel Schludi on Unsplash