Managing Forest Fires: Destructive Legislation vs. the Wisdom of Fire

In light of the Milei government’s Urgency Decree and Omnibus Law – regressive legislation designed to limit democratic power as well as human and environmental rights – Cecilia Lis García reflects on what this relationship to fire says about humankind. Since publication of this article, both measures were approved in a devastating blow for Argentina. In another tragedy, the offices of Revista Anfibia in Buenos Aires were destroyed by fire just two months after the publication of this essay. Whether this was a targeted attack or result of faulty construction remains unclear, but in either case it underlines the point that our relationship to fire is fraught and in need of healing. To support Anfibia in recovering from this devastating loss, donations can be made here.

There seems to be no end to media reports about the invasion of forest fires into native biomes. Preserving these habitats can certainly be counted among our most urgent needs, though if the Necessity and Urgency Decree and the Omnibus Law are passed, emerging wildfire hotspots will no longer receive the relief and assistance they need from relevant public bodies. This is not only a question of our forests going up in flames, but also an uncomfortable reflection of our relationship with nature and with each other. How does fire challenge us? Is it too late to come up with new perspectives, a more integrated vision of what fire means as a natural entity, inextinguishable and undefinable in the face of all the dehumanising forces surrounding it?

Quebrachos, itíes, locust trees, caraguaratás, palm trees, peppercorn trees, floss silk trees, aromitos and jungleplum trees. These species that populate the Gran Chaco have evolved and adapted to geological changes. Visit any natural habitat in the region and you will find forests of plant and tree growth covered in thorns – a natural defence against drought. These trees also contain sap, which they distribute throughout their leaves and thorns in order to endure periods of dryness. Plant life can adapt to anything, to any temperature except the extreme heat of fires. When faced with flames, trees become fodder to the voracious appetite of a fire that expresses much of nature’s hidden power.

Chaco is home to one of America’s most important forest biomes. This summer the threat of fires luckily waned, perhaps as a result of recent efforts to defend our forestland: areas left standing were mapped in order to plan their conservation; forest firefighting brigades were fitted out with proper equipment; an environmental risk area was established in which drought records and heat sources at risk of causing fires were monitored every day; new nature reserves, national parks and protected areas were established; biodiversity corridors were set up; and trainings were held throughout the province on the reality of the ecological and environmental situation. These actions were driven by the Secretariat for the Environment and Sustainable Land Development, the continuation of which is now in jeopardy due to the new government’s denialist position on climate change. Forests outside this region, however, did not receive the same protection under the law. Nevertheless, according to a new report by Greenpeace, in 2023 Chaco surpassed the annual record for the largest deforested area in Argentina.

The sound of fire grows louder as the wind picks up speed. Its roar feels very close, even though it is burning several kilometres away. Billowing clouds of smoke act as an alarm, a contagious cloud of death and transmutation that obscures the stars, trees and houses. The next day, a blanket of grey and its charred smell, dragonflies, pirincho and carancho birds – language and loss overlap, reflecting what it means to inhabit this impenetrable land.

Recently the media has highlighted the impact of accidental fires on native biomes, which, in turn, are in a constant state of risk. In Argentina and in Chile, the advancement of the forestry business and the techno-capitalist boom create complications for the rescue and regeneration of these forests, despite the urgent need to preserve them. The same thing has happened in Canada, Australia, Greece and Hawai’i. All of these incidents that we witness in shock, again and again, are the result of the cyclic relationship between climate change, human greed and indifference, as well as the speculative practices and violent corruption of governments worldwide. Vast swaths of native forestland, once a source of and refuge for biodiversity and vital coexistence, are becoming leftover relics warped by a literally suffocating and heartbreaking onslaught of human activity.

What, then, is our perception of this being, this entity called fire in all its dimensions and intensities? How can we find a way to coexist with it with respect and care, with an eye towards the preservation and protection of the planet’s other life forms? The key is to cohabitate in networks, to ponder, imagine, create and take a chance on new options that could help us to realise a more integrated and conscientious vision of what fire entails. After all, fire is part of the line of production for inevitable technological devices in this technocene era. It is part of environmental change and the epistemic crisis of perceptions. Fire is also a natural entity, inextinguishable and indefinable in the face of all the dehumanising forces surrounding it.

Fire is also a manifestation and reflection of contradictory values.

“Fire suggests the idea of changing, of flattening time, of pushing life to its end, to the afterlife (…) Fire and heat supply a means of explanation in a vast array of fields because, for us, both are a source of enduring memories, of personal, simple and decisive experiences. Fire is a privileged phenomenon that can explain everything. If everything that changes slowly can be explained by life, everything that changes rapidly can be explained by fire. Fire is beyond alive. It is intimate and universal. It lives in our hearts,” philosopher and poet Gastón Bachelard wrote in The Psychoanalysis of Fire in the 1970s.

Hey, hey, hey. Don’t fall asleep.

Santiago Motorizado lays out a Promethean beat, that Argentine spark. The song Fuego echoes through the air, flowing more vibrantly than ever, out towards the patio, to the plaza, the sky, to the Yunga highlands and their mountains.

Can we take this moment of internal connection as an opportunity to calm (or suffocate) our anthropocene aspirations, draw inspiration and commit ourselves to solidarity, to being gentle once more, to understanding and discerning in the midst of this seething heat, and derive from our separate lives some common path forward? The wisdom of fire has its own ways of teaching, its own truth, as it crescendos to reveal the real problem: our culture of Western decadence.

The whole universe depends on this.

The whole universe depends on this.

The whole universe depends on this…

When the smoke spreads, it covers the sky, the mountains, wetlands, wildlife, cities, homes and families of every species. It makes it impossible to go out for a walk without feeling dizzy, coughing or struggling to breathe or even see ahead of you. Without remorse or respite, the flames reveal the inconsistencies of our herd and its way of life.

Resistance has emerged in forms such as the Multisectorial Humedales de Rosario and its coordination team in defence of the Paraná Delta river basin (which saw more than a million hectares of its land burn to ash during the pandemic), initiatives run by the Asamblea Correntina Basta de Quemas and NGO Defensores del Pastizal in Corrientes. In Córdoba, Unides por el Monte, Asamblea por el Monte and Arde Córdoba show how the affected population is also coming together, creating spaces for civil resistance to unite farmers, beekeepers, artisans and the public at large, including municipal and provincial officials. All of these efforts are aimed at stopping the continued devastation and declaring a state of emergency – not only economic, but also environmental.

If Javier Milei’s Necessity and Urgency Decree and the Omnibus Law prevail, it will mean the end of the Official Daily Reports on Forest Fires – new outbreaks are already underreported or simply ignored by relevant government bodies. Law 26.562 on Minimum Budgets for the Control of Wildfire Activities is also being cut, leaving our forests and woodlands vulnerable and tacitly authorising the burning of forestland to create fields for productive purposes. Moreover, the continent is already left with the irreparable scars of Bolsonaro’s political and material handling of wildfires in the Amazon, which all but suffocated one of the most essential biomes for the development of life on our planet. The devastating results mean more droughts and imbalances in the Earth’s womb as well as her sacred, biodiverse rivers and bodies of water.

In addition to Santiago Motorizado, my playlist also includes Horacio Salgán together with the Orquesta Filiberto. A fuego lento (“Slow burn”): a tango that, according to Salgán, came about in an “‘obsessive’ musical climate, constantly listening to classic milonga standards. After the melodic part, it goes back, until the end, building that pulsing, captivating rhythm that makes it so unique.” By leaning into the urgent forces that drive Salgán’s music, we too can reach a critical, creative breakthrough to help us understand the constant threat that scorches our land, homes, lives, futures.

While our Western culture views fire through the lens of its Greco-Roman origin myth in the deformed yet skillful figure of Hephaestus (the god of fire), the epistemologies of our indigenous communities express reverent and silent respect for it, placing it at the centre of the whole community (ritual fire) and at the heart of every individual (spiritual fire).

In this present time of conflicting anthropocene desires, of crossfire in unprecedented conflicts, fire crystallises and transforms the memories of everything it devours and dissolves. Cities and territories burned on the same pyre, as in the count-down ritual of ashes that Cortázar recounts in All Fires the Fire: “It’s going to be hard. There’s a wind from the north. Let’s go.”

Panta rhei: everything flows and flows again. Heraclitus and the stoics made this element and its transformative essence into a cosmogonic principle. Another of our culture’s founding myths tells of Prometheus and how he bestowed fire unto us as a means of propagating and accelerating human life. From this episode of cultural evolution we should also understand the need to refine our knowledge of fire in order to stop fearing it, to learn to drink from its empowering synergistic qualities instead of fleeing from their consequences.

Contemporary forest fires are not only a problem of trees going up in flames. They are an uncomfortable reflection of our relationship with nature and with each other.

Gaia and her dynamic cycles, utterly incomprehensible from a position of techno-human apathy and ignorance, will outlive us. Planet Earth will keep pulsing, throbbing, living, something that we cannot guarantee for ourselves as a species. An ever-changing world constantly raises new questions. What are we going to do with all of this calculated negligence? Will we be able to organise humanity in order to take care of ourselves and prevent future fires? Do we still have time to make these decisions, or will our powers of discernment be extinguished in the process of evolution?

![]()

Produced by Guerrilla Translation under a Peer Production License

– Written by Cecilia Lis García

– Translated by Timothy McKeon

– Edited by Alex Minshall

– Header image by Pablo La Padula

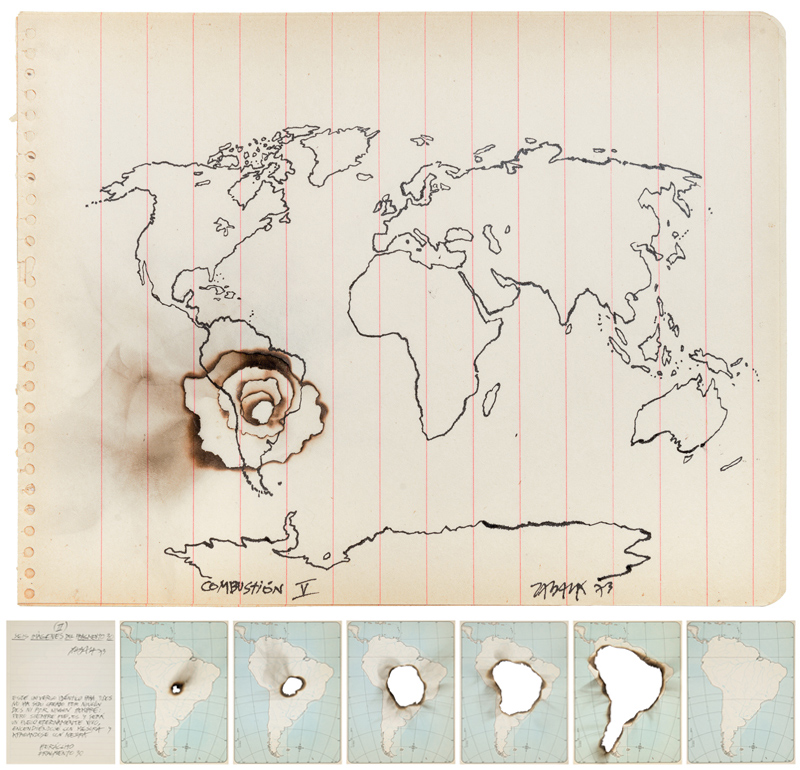

– First in-text image: Combustión V 1973 – Seis imágenes del fragmento 30 (II) Políptico 1973 by Horacio Zabala

– Second in-text image: Cenizas del Paraná by Electrobiota – Gabriela Munguía (MX), Guadalupe Chávez (MX), exhibited at Festival Ars Electronica 2022 – Linz, Austria, photo by Florian Voggeneder

– Thirs in-text image: Cuerpo de humo y fuego by Pablo La Padula, exhibited at Trans humo, Macba 2023, Buenos Aires, Argentina

– Original Spanish language version published by Revista Anfibia