My Debt to Spain

Pablo G. Prieto describes himself as “a scientist working on the science of a post-capitalist world”. He is also member of the Catalan Integral Cooperative and FairCoop. In this short piece, he expounds on his ongoing “relationship” with the Kingdom of Spain. As you’ll see, “it’s complicated”.

I received a thick envelope from the Agencia Tributaria del Reino de España – the “Tax Agency for the Kingdom of Spain”. Inside, there were pages and pages full of two-color charts, pretty nice. What they offered me – for free – was a thorough breakdown of all my outstanding fines since the 12th century, more or less.

That I got this letter isn’t news: they’ve been diligently sending me notices every six months, renewing the fines they impose on a regular basis so they don’t lapse and expire on me. These fines aren’t the kind for the bigshots; those expire in five years. But here’s the real news: for the first time, my debt had exceeded the figure of ten thousand antique euros (some 22 BTC, at time of writing). Strike up the band!

The Kingdom of Spain granted me, in a grand display of democracy, the freedom to chose from among three options:

a) All fines to be paid in full, plus an additional penalty (substantial) for having been in default for so long.

b) Deduction of the amount from my bank account, without my consent.

c) Use of this debt judgment to try and coerce me in any other context, at any given time in my life.

Two out of the three options are based on using violence and power. Fortunately, I don’t have a bank account, and I have less and less dependence on the State all the time. Looks like they’ve got no way to stick it to me, as my Argentine neighbor would say.

What does it mean to have €10K in fines? It’s money that never existed, so it can’t be claimed as missing from somewhere. If I paid, would it create wealth? Increase GDP? Socialize wealth, perhaps? Or only change hands? Whose hands are better?

And what if I don’t pay? Presently, I’m in a position to swear before a judge in court that I do not have this amount of money. Nor will I: whenever I get money, I immediately invest it in things which I’d like to see thrive. I’ve got nothing left. I only hope that, in the end, things do work out for me.

I enjoy a basic income from the cooperative I belong to, which also covers almost all my necessities. Money isn’t a problem for me. What’s more, I could come up with 10K pretty easily. But obviously, if this is what it’s for, well, no.

I don’t know if the State counts this socialization of private wealth as an asset, a liability, as debt, or whether it’s included in the general budgets. I’m not really clear to what extent they expect to receive it, and no idea why they want it. I’m unaware if they’re counting on it to end the crisis. I don’t know if on account of me, someone is going without a pension, a wheelchair or a school lunch. Maybe I am a fraud and should be punished.

What I do know is that if one day I say, alright, I’ll pay my debt, I won’t be able to pay the State directly. I’d have to give it to a private bank, which would use it as seed money to create new money – to benefit all kinds of evil projects along the way. Then the Bank will hand it over to the State, and they’ll return it to the Bank, by one of their many means of doing so.

The State and the Bank are practically the same thing! Stop, just stop. It’s better if I manage my own money.

So, what are those fines for? Well, they’re for disobeying unjust laws, laws I took no part in creating. For practicing democracy instead of requesting it. For doing my civic duty, which doesn’t come cheap.

Produced by Guerrilla Translation under a Peer Production License.

– Translated by Stacco Troncoso

– Edited by Ann Marie Utratel

– Original article published in the Spanish edition of the Huffington Post

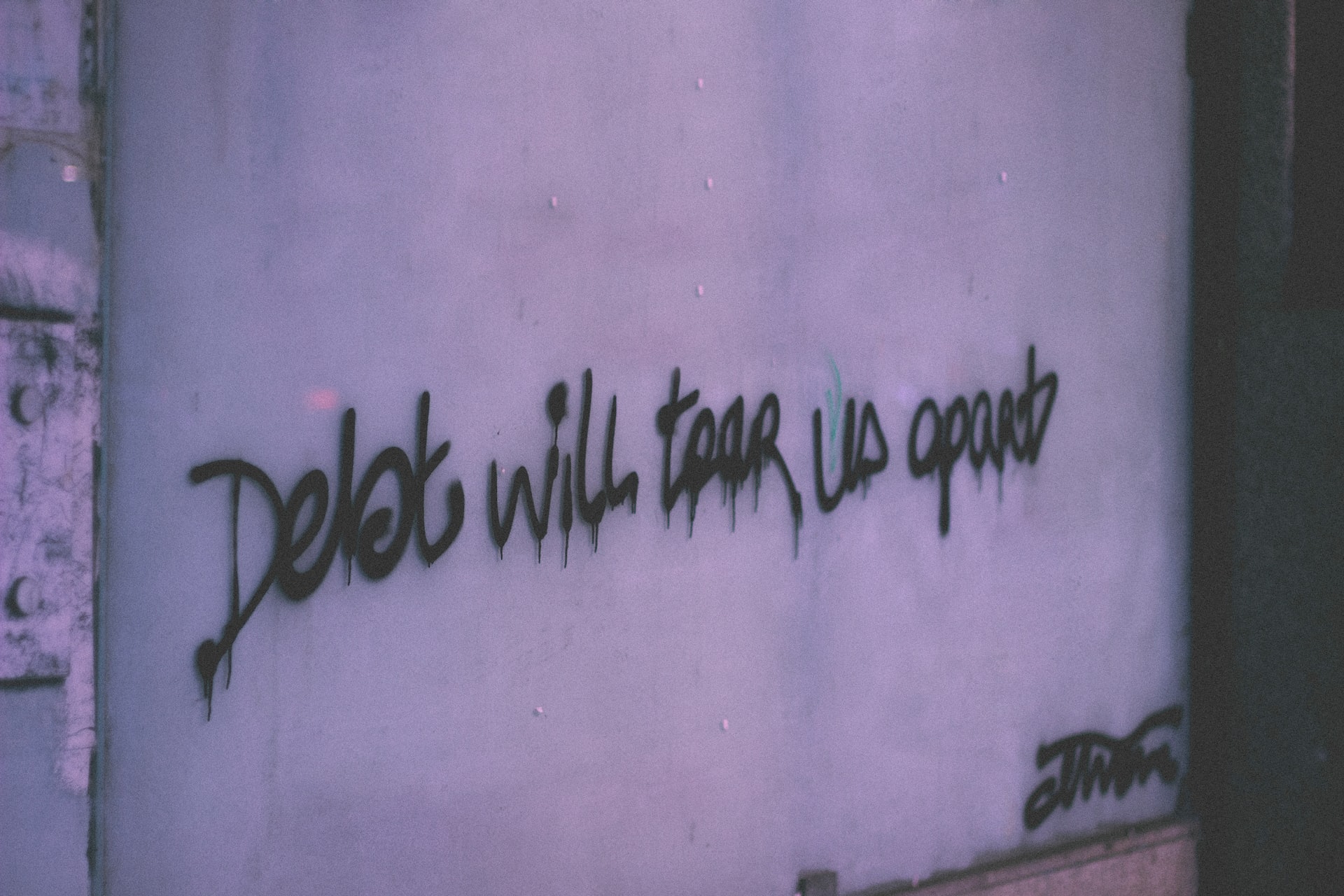

– Photo by Ruth Enyedi on Unsplash.