What is the sound of a river paved over? A sound map of urban rivers in Buenos Aires and La Paz

This article, by members of the Field Recording and Sound Map Workshop (Spanish acronym: TGCMS), was originally published in Argentina-based magazine Anfibia. It was selected as part of our second Lovework Open Call. Sitting at the intersection of art, ecology and ethnography, it shines a poetic and sensitive light on the subjugation of nature to urban development, and we hope it will help to change the way you see the built world around you, as it did for us while reading and translating it. Artwork by Colectivo Nudo. You can read the original piece in Spanish, which also includes audio recordings from the project, here.

Recently, the streets of Buenos Aires have been filled with posters and graffiti depicting sky blue waves, marking the location of streams and rivers that are now channelled through underground pipes. Artists and academics from the Field Recording and Sound Map Workshop (Spanish acronym: TGCMS) came out to record and survey the sounds that these rivers make. They cannot be seen, but can they even be heard? This action reflects on the acoustic surroundings in our hyper-urbanised cities: the roar of a conquered, subjugated ecosystem, post-naturalism, wetlands, white noise, and the utopia of silence.

Aguas abajo, Mapa Sonoro de Arroyos Urbanos (Waters below: a sound map of urban streams) forms part of the Second International Art + Science Congress entitled “Las aguas” (The waters) organised by the Centre for Art and Science at the UNSAM School of Art and Heritage. It was carried out by María Ximena Arqueros, Miriam Djeordjian, Camila Juárez, Andrés Villegas and Pablo Bas.

***

It is strange to map the sound of something that is absent. Even more than absent: imperceptible to urban life.

What sound does a river make when it ceases to be a river?

Water is a vital element, yet Buenos Aires is notorious for turning its back on its rivers, for condemning them to the underworld. Many of them crisscross the city’s terrain: Vega, Medrano and Cildáñez are just some of their names. They are there, but running through tubes under the ground. Invisible.

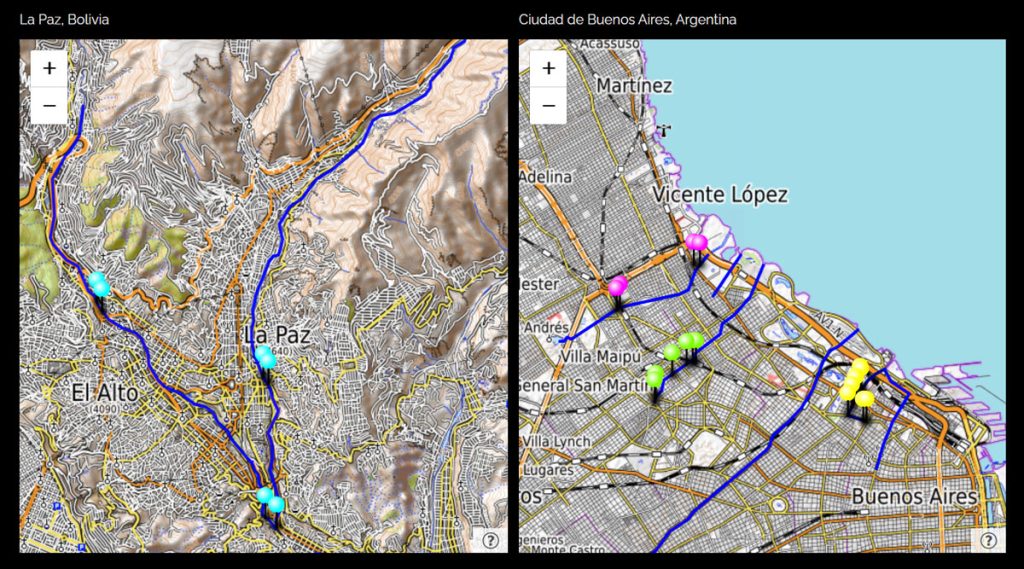

In the TGCMS, we decided to collectively locate, listen to, record, edit and map the spaces in which we lived and moved, all with a common goal. We wanted to learn about the water in our neighbourhoods and landscapes in Buenos Aires (Argentina) and La Paz (Bolivia). In an exercise of sonic imagination, we set out armed with professional recorders and mobile phones alike. We focused our exploration on crossroads, pausing among the watercourses and the movements of people in public, liminal spaces. The journey inspired questions, triggered doubts, allowed us to access that pulsating threshold living so close to us. Aguas abajo, Mapa Sonoro de Arroyos Urbanos (Waters below: a sound map of urban streams) records (in every sense) the soundscape of our hyper-urbanised cities, a census of the smell and the roar of a conquered ecosystem. It documents the invisible water catchment areas of Buenos Aires, and speaks to post-naturalism and the ecology of the landscape.

Recently, signs pointing to this hidden underworld have been popping up across Buenos Aires like mushrooms after rain. Round placards with blue waves have been attached to lamp posts, signs have been painted on zebra crossings and encircling manhole covers, proclaiming:

― The river X flows through this place.

First you see the sign. Then you process it. Allow your senses to mingle, let the letters filter through and trigger your intuitive memory of the natural environment.

Ask a civil servant about these “tube rivers” and you will be swiftly corrected. “No no,” they will say, “these are not ‘tube rivers’, they’re underground streams.” Ask Latin American political ecologists, however, and they will speak of the neoliberal city, about dispossession, about water as a key measure of inequality. There is a very good reason why public policies around access to drinking water and flood prevention can make or break an election.

Urban development creates new geography: it places signs, machinery, pumps, and rusted cages where once there was flora, fauna, mud, puddles and flowing water. It creates socio-technological entanglements between the human and the non-human.

In the city of La Paz, the Choqueyapu and Orkojahuira rivers are also in the process of being channelled through tubes. This has not escaped our attention either.

Ebb and flow. Green light: bikes and cars traverse the concrete above the stream. Red light: a pause before pedestrians make their way across. The car wash with cars waiting, music in the background as traffic flows all around.

Recording the sounds of a river that ceases to be a river is like digging up your ancestors to shout at them, to tell them that we can’t live without their stories. Because they’re our stories too. These water signs – like the star-shaped ones placed to remind us where someone was run over and killed – stand in contrast to other public road signs that surround us.

The river runs through a tube, hidden from our senses but not dead. Its torrential, material waters flow through a quasi-disciplined subterranean world, and every now and then it reappears and says, “Here I was.” The victim reacts and it disturbs us. It floods us, it overflows us, it commands great contradiction. Being a secret is tiring. It tries to reveal itself through sound. It bears witness to the geo-bio-laboratory that we have made of our own home.

How can we draw a map of invisible territory? Why map sounds that cannot be heard?

“If the map is an image that shows the way elements relate to one another in space, and those elements are not geographical, then the map becomes a metaphor, a form of spatial knowledge.” These are the words of geographer and philosopher Carla Lois, one of the many authors whose work we have read to try and understand the ethnographic paradigm in which we are submerged.

These rivers – dirty, forgotten, an obstacle to be overcome – at some point began to share space with the cars and people who move on the ground above them. They can perceive each other, they can hear one another. One is quiet and secret, the other arrogant and overbearing. They share a point of acoustic contact, a familiarity: white noise, the sum of all audible frequencies that appear when torrents of water and vehicles rush over one another.

Transits and barriers. The Saturday afternoon shopping fever grips the street, while cars and bikes go past a bar. Afternoon settles in.

Our existence is made of ceaseless movement, a flow of forces that circulate. Vibrant, delicate, brutal, lurking. Stillness doesn’t stand a chance, nor does quiet. Movements can be heard, because sound is movement’s witness. We feel these movements in our bodies, we reason them into being and call them sounds. Our aural being makes sense of the world around us.

Movement cannot be stopped. Sound is always being made, it never rests. There is always something to listen to, even if it’s just our own breath, the final defence against silence.

Reviving these subterranean waterways through sound art reveals the memory of wetlands that were silenced by the city’s spread. Sound maps and counter-cartographies bring new languages to environmental education, they sidestep the visual onslaught and invite us to awaken within ourselves a new, poetic, political form of attention.

Produced by Guerrilla Media Collective under a Peer Production License.

– Translated by Alex Minshall

– Edited by Timothy McKeon

– Original Spanish-language story published in Revista Anfibia.

– All images, including the lead image by Colectivo Nudo, taken from the original article, with captions translated.