Puta Influencer

The following was originally published in the Spanish-language zine Descuartizadora, which Guerrilla Translation is translating into English as part of our first Lovework Open Call. Individual articles and poems will be translated and posted here one by one until all the content has been completed, at which point an English-language version of the zine will be formatted and made available in its entirety.

“I’ll give you my Whatsapp”

Out of all of the anxiety-producing situations I get myself into, one of the worst is when I lose my cell phone. Whenever I lose my phone or it gets stolen, I feel like I lose clients, I lose my most basic work tool. I don’t work the streets, so it’s not easy for me to just go out to a street corner and offer my services without relying on Whatsapp. My clients ask me for pics – I have online clients who transfer me money in exchange for homemade porn. When I don’t have my phone, I lose all those clients and all those videos. Luckily, it’s not that hard to get a new one. Everybody’s got one. Recently I was given a new cell phone after I was spotted fighting in the street with someone who broke my old phone in an act of revenge (they knew they were destroying my means of livelihood). What bothered me most that evening was that, in an instant, I suddenly had no way to get online. A guy working in a nearby café helped get me out of that dangerous situation, and after I told him all about it, he gave me a new phone.

Luckily he sympathized with my line of work and understood how urgent the need to make money can be when you’re poor in Santiago de Chile. My clients are used to me changing phones. I don’t get the same number back; I just buy another SIM card. A new SIM card for 1,000 pesos and then I update my social media. My blog (el blog de Camilo) is the first thing I update with my work number. Then Instagram, Facebook and profiles on gay escort websites. I guess the hyper-mediated nature of social media might scare away some clients looking for discreet prostitution in such a prudish and heteronormative society. Still, creating content that goes viral – something you can only do online – becomes really important when the freedom to do what you want with your body is prohibited and criminalized: in this case, selling sex. To me, Instagram was just a digital school for contemporary sex work. As feminist putas (Spanish for whore, slut, ho, etc.) working online we’re not only reeling in clients (though that is our top concern, otherwise we don’t eat), we’re also claiming visibility in a world that wants to banish us to the dark corners, keeping us servile, hidden, silent, obedient. A disobedient puta is no different than any other puta, she’s just got a different approach to sex work. And in the era of social media, any puta online is a disobedient puta. Part of our cyber-activism, of my activism both in CUDS (University Collective of Sexual Dissidence) as well as Emputesidas (a trans-border, multimedia sexworker collective), is to cause a scandal and go viral with our puta mindset. Our desires and what we do. Our aesthetics and voices as online vectors of viral seduction. This is what makes me a puta influencer. Giving advice on Instagram, offering services and answering questions in my stories. You’ve got to stand your ground, because these spaces don’t make any room for sex work. Even Tumblr, which was turning into a kind of new platform for porn, had to reconfigure its regulations to explicitly prohibit pornography and prostitution. Same thing with Instagram, which explicitly states in its rules that offering sexual services is prohibited. They delete our images and videos, report us and block our accounts. They’ve frozen my account so many times I’ve had to figure out how to advertise in a more subtle and indirect way. On Grindr I’ve been reported enough times that I don’t use words like services, money, puto, cash, etc. And on top of it, people online, whether on Grindr, Instagram or Facebook, love to play internet police. Consumer control.

For the same reason and because of this system of using the internet as an alluring trap to control digital society, sex work in the digital world has huge potential for subversion. I think of Digimon when I think of us, because we aren’t the VIP or jock version of cyberprostitution. We don’t have any problem with sex workers with jock bodies, but they’re clearly not the monsters that we are. We’re digimons. We live in a digital world and have outbursts that can get pretty heated, but also very scary. Outbursts not just towards the hetero world, which can be expected, but also towards fellow putas who are discreet and obedient as well as others throughout the spectrum of sexuality. After all, feminism isn’t lacking in digimonsterphobia. But in the case of abolitionist feminism, more than a form of hate, it’s a discourse, a political conviction, an ideological tenet to stand against sex work and fight to make it disappear. We all oppose sexual abuse and rape. None of us defend human trafficking, non-consensual torture or the sexual exploitation of children, but abolitionist feminists keep associating us with the unjust treatment of people in order to argue their own point of view. They insist that women who are putas don’t have the capacity to discern or decide for themselves. Although so many of us putas are using our puta bodies to reclaim what we call sex work (whether online or otherwise), they continue to speak out from a comfortable distance, framing us as victims in order to say no to prostitution. One of the things I hear most from these colonizing feminists is that women are exploited, they reproduce machismo and are accomplices/victims (make up your minds) of the patriarchy because they continue to maintain a way of thinking where the woman is the serving wench and the man is the consumer.

The audacity of online prostitution at a time when social media is succumbing to family values and the anti-porn/anti-sex work agenda constitutes a porn offensive. The pedagogy of the Instagram puta, stories with special offers and XXX videos, tips on how to become a cyber-puta in under five minutes, going viral despite Instagram’s anti-prostitution regulations, and many other things, all set cyberprostitution up to be a bastion of sex-positive feminist resistance instead of just a desk job with a webcam. But is the online virtual version of our work just sanitizing prostitution? Maybe the media and the “professional” world are once again just trying to clean up a group that seems too subversive and volatile, since it’s no longer that dangerous to pick up a puta on the street. It’s even “cool” to support internet putas that don’t have any sexual contact with their cyber-clients. We feminist cyber-putas need to be aware of this movement that’s taking up arms against us. Abolitionism is one thing, performing propriety is another, and the farce of Chilean propriety will always create hierarchies. We won’t. We are all equals. Format doesn’t matter, even when it comes to standing together in the same struggle to demand recognition as workers in a country that consumes us but refuses to accept us as legitimate members of society.

![]()

Produced by Guerrilla Translation under a Peer Production License

– Translated by Timothy McKeon

– Edited by Alex Minshall

– Original Spanish-language article published in Descuartizadora 1

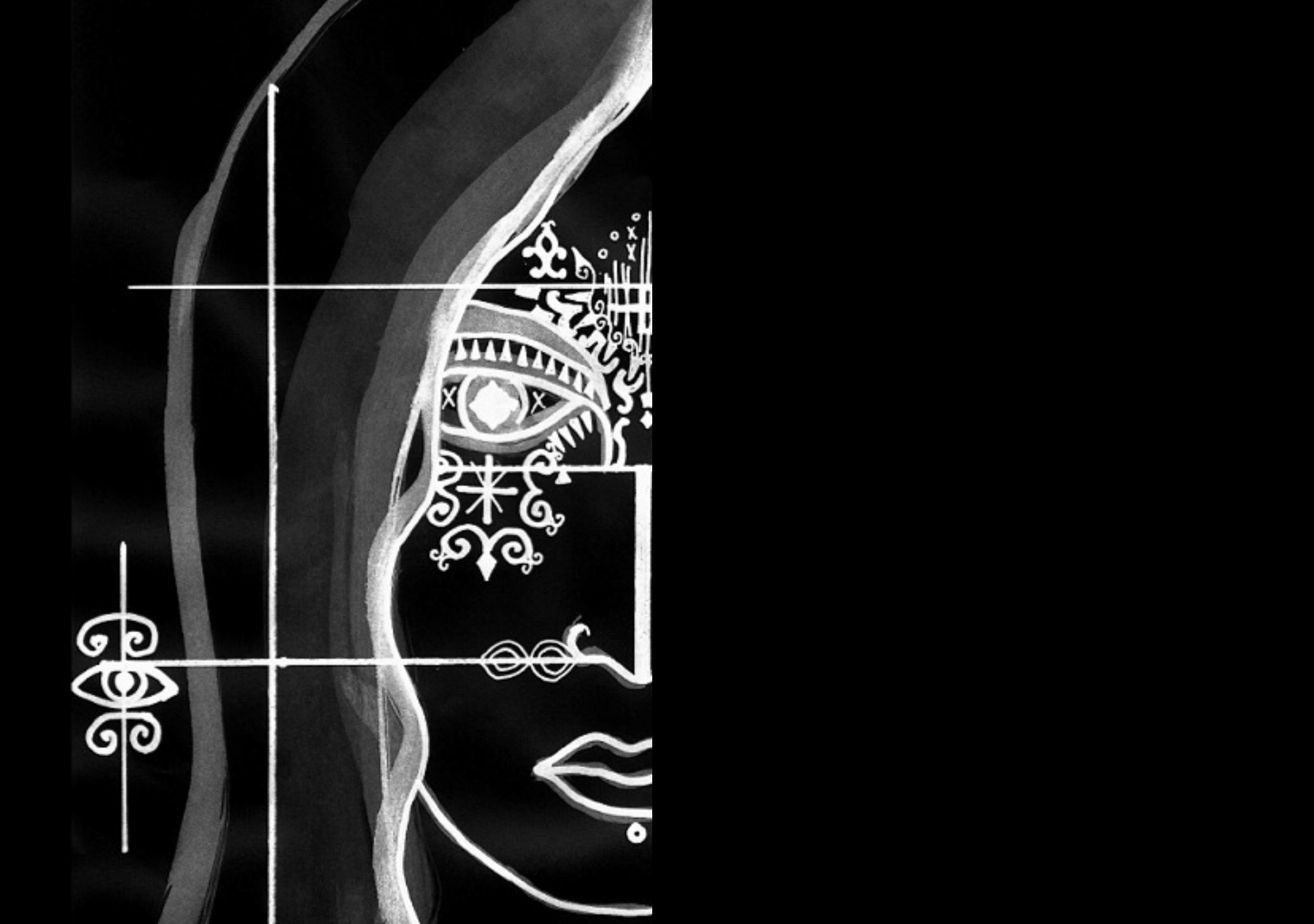

– Images taken from Descuartizadora 1, lead image by Nahuel Neira